Just yesterday someone handed me a flyer for an incredible offer. Learn 1000 foreign words in a week, from scratch. The flyerer showed me prestigious tricks to remember the sequences of letters -the foreign words, precisely- and I was about to accept the proposal and boost my Dutch once and for all. Later, while walking home, I was wondering what would be the benefit of knowing so many words, without the ability to compose them together in a sensible way. Maybe, I would be able to understand what someone is asking me, recognise the term in my vocabulary and then respond by pulling out another item from the list. But could it work for a real conversation?

It is rare to hear words on their own. Usually, they come together in groups and their combination is important. For example, if we read: “the dog runs” we must know the meaning of both “dog” and “run” to picture the animal and its movement! Sometimes, even their particular arrangement carries meaning, as in “the mouse bites the cat”. Because words are the atoms of speech, we must put them together in sentences if we want to enjoy the full power of human language. And this makes things complicated for my 1000-words vocabulary flyer, especially during a real conversation!

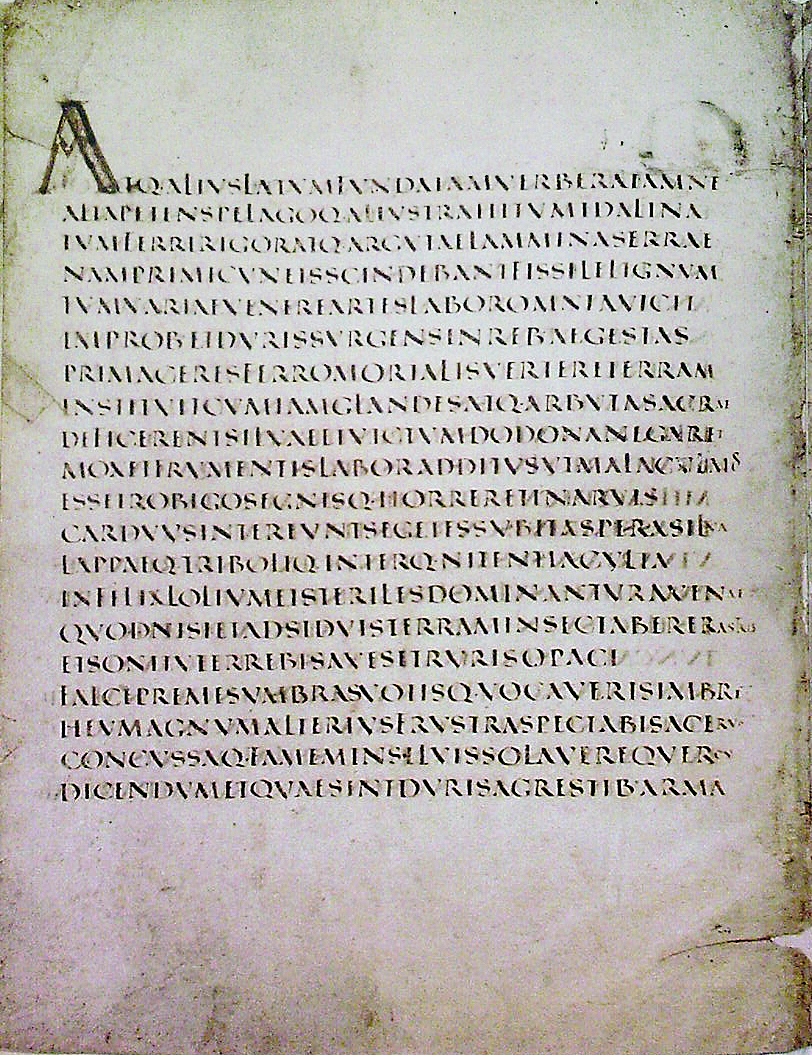

The magic of segmentation is to identify words in the stream of sounds, in real time, with our speaker talking to us. We recognize each word that was pronounced and search for them in our mental dictionary to get its meaning (read more). This process is fast and robust. It takes about 200-300 ms to recognize each word and even works when speech is obscured by noise, for example in a bar. Segmentation is an amazing ability and largely depends on the proficiency with the language, but it is not independent of other aspects of language use. In order to grasp which words were used, we leverage the knowledge of the speaker accent, their non-verbal expressions and ultimately the context of our conversation.

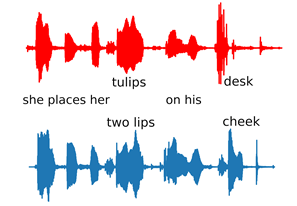

So, what happens when we purposely play around with our segmentation ability? Let’s take an example and record an Australian speaker while pronouncing this:

She places her tulips on his desk.

You will get something like the oscillogram figure here. An oscillogram is a visual portrayal of a sound wave. Large bursts mean that sound is present, whereas a flat line indicates a silence. In the oscillogram you can see that the bursts of the parts ‘tulips’ and ‘two lips’ are very similar. This means that although they are different words and even a different number of words within the parts, the sound these parts make is the same. Only at the end of the sentence, when we would hear ‘desk’ or ‘cheek’, we know for sure whether the sound in the middle was ‘tulips’ or ‘two lips’. Without this final word, the sentence would be ambiguous and hard to understand.

The example above, and similar sentences, were used in experiments to show that when we hear ambiguous sounds that could refer to multiple words, strange things happen in our interpretation of that sound.

To make things clear, let’s try to imagine what can happen in the mind and the brain of the listeners just after hearing the ambiguous sounds. There are two possibilities. First, they get only one of the two meanings, the flowers (tulips) or the kiss (two lips), based on experience with these words or personal bias for one word over another (maybe the listener works in a flower shop). When at the end of the sentence they realize they have picked the incorrect meaning, they correct their expectations with a bit of surprise. This is quite an economic and reasonable way to proceed, but experimental evidence supports another view. Psycholinguist research showed that listeners activate both the words in their mental dictionary that could fit the ambiguous sound, and pick up the right one only when there is enough information, at the end of the sentence, when sure of the correct interpretation. These experiments tell us that we keep two images in mind, at the very same time, until one is proved correct. Wait. That is cool!

The science of words provides us an intriguing starting point to unveil the mysteries of language and the magic of its usage. A subtle aspect we did not make explicit in the example above is that often the listeners are not aware of what is happening between their ears. If we ask the participants what words they heard, they will not report the one that did not match the context (flowers → desk, lips → cheek). The thought traversed their mind unconsciously, just for a second, abandoned when the upcoming words disambiguated it. But does it influence the mental image we have of the other concept? Will the tulips in the example be more sensual than the usual tulips? To answer this question we will look to other fields of human knowledge, that belong to the arts and occult more than to the science: poetry and alchemy.

We all know that words are extraordinary in the hands of poets. They use them like rhetorical devices, or figures of speech, to convey atmospheres and meanings that are beyond the linguistic level, for example using long words with smooth sounds to inspire tranquility. Language tricks enrich the experience sprang to the mind of the reader, but sometimes these devices can be used to go beyond the beauty of poetry and move into shady business. Although the experimenters had no personal reasons to trigger two thoughts, this human disposition can be used to persuade someone with the power of mental images, or to hide meanings within an apparently innocent sentence.

This is the case of the Langue des Oiseaux, a French hermetic language spoken by intellectuals and alchemists in the modern age (1500-present). It must be noted that consistent sources for this topic are hard to find, and even the Wikipedia community struggles to provide sound references to the entry. When dealing with esoterism, it’s often difficult telling apart historical facts from opinions and rumours. Nonetheless, it is a fact that the Langue des Oiseaux was used to conceal -and enjoy- double meanings. Differently from the other argots (slangs) -like the verlan-, the Langue des Oiseaux was a secret language that played with the words without changing them. Indeed, the Langue is all about choosing words with ambiguous sounds and stressing sub-structures within the word or adjoin two words to form another one. For example:

‘You see if a wise dish is created, said without words’

can be heard as:

‘Here is a secret message, saying the words’

To take part in this game, speakers had to train their abilities and the mysteries of the Langue were not available to anyone but the initiates. Moreover, the sentences were often obscure in both the superficial and hidden form: if you would have completed the difficult task of finding the right double words, the true deeper meaning would still be concealed due to the alchemists’ tendencies towards hermeticism and opaqueness. Each word was loaded with multiple meanings, creating a connection between word’s pronunciation and meaning that was much tighter than we conceive nowadays. If you want to delve into this mysteric world, this website reports many hidden meanings of the Langue, however, we would not take it too seriously!

In the end, we have seen that the human language is rich in secrets, and many of them are still to be discovered. The most fascinating of science is when it explains phenomena that seem deemed to be the realm of magic, and it shows that our brain is intricate enough to contain all the supernatural we could ever imagine.

Read more

– Gow Jr., D. W., & Gordon, P. C. (1995). Lexical and prelexical influences on word segmentation: Evidence from priming. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 21(2), 344–359. Link

– McQueen, J., & Gaskell, M. G. (2007). Eight questions about spoken word recognition—Oxford Handbooks. The Oxford Handbook of Psycholinguistics. : Oxford University Press. Link

Pictures

– Scriptio continua via link

– Example two lips/ tulips: own production

Writer: Alessio Quaresima

Editor: Naomi Nota

Dutch translation: Leah van Oorschot

German translation: Natascha Roos

Final editing: Merel Wolf