As complicated as French

I used to take violin lessons in French, and during my lessons I used the formal pronoun “vous” for my teacher. I did this not because it was grammatical, but because it’s respectful. As discussed in the previous post in this series, this is true for gender too: the pronouns that we use for people typically have more to do with respect than with grammar.

My violin teacher appreciated being called “vous”, but attitudes about the use of formal and informal pronouns vary from person to person and have shifted over time, as many French speakers can describe at length. This too, happens for gender. When we as a society start to think differently about gender, the way we use gendered language shifts too.

Swedish provides a great example of this with the pronoun hen.

This hen is gender inclusive

In the 1960s and 1970s, linguists and legal scholars in Sweden proposed the use of a new pronoun hen as a gender-neutral pronoun to be used when someone’s gender is either unknown or unimportant. They argued that this new pronoun would be shorter than a phrase like han eller hon (‘he or she’) and more inclusive than using han (‘he’) as a default pronoun (Milles 2011).

Throughout the 90s, hen gained traction in feminist, queer, and transgender spaces, and its use expanded. In these spaces, people used hen not only as a gender-neutral replacement for han eller hon, but also to refer to specific people with fluid gender identities or identities outside the dichotomy of male and female (Milles 2011).

Breaking into the 21st century, hen was increasingly adopted by publications and institutions as a gender-neutral pronoun. Eventually, it was in wide enough use that the Swedish Language Council endorsed it in 2013, and it was added to the Dictionary of the Swedish Academy (SAOL) in 2015 (Gustafsson et al. 2015). Although it still felt new to some speakers, hen was clearly here to stay.

Small changes can have big effects

It’s been over a decade now since hen became official, and as you might expect, it’s become as standard as any other part of the language (Gustafsson et al. 2015, Vergoossen 2015, Gustafsson et al. 2021, Vergoossen 2021). But that doesn’t mean it’s had no effect.

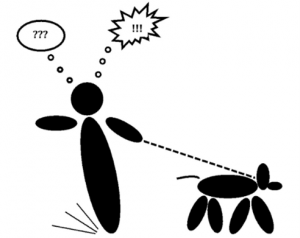

The effects of a language change like this can be surprising. In one study, researchers Margit Tavits and Efrén Perez asked Swedish speakers to describe pictures including an ungendered figure, like the one above. Then they asked them to imagine meeting a new person who’s running for political office. What would that person’s name be, and what would they be like? The researchers found that when participants used hen to talk about the ungendered person in the picture, they were more likely to give a non-masculine name for the new person they imagined than the participants that used han (‘he’) were.

Later, when the researchers asked participants to name politicians that they knew, participants who used hen were more likely to name woman politicians, and in another follow-up survey they were also more likely to express positive opinions about the presence of women and LGBTQ people in public life (Tavits and Perez 2019).

In this way, hen opened up a space for Swedish speakers to think more readily about people with a wider variety of genders, and consequently, to be more accepting of a wider variety of gender expressions in society. What a positive impact for such a tiny word!

But what about other languages? Is Swedish just an exception? And what does your brain do with neopronouns? To find out, check out Pronouns in Bio, Pt. 3: What the brain can teach us about pronouns.

Bibliography

- Allison, M. C. (2018). G “hen” der Neutral–How Sweden is Furthering Gender Equality Through Language. In Rhetorics Change/Rhetoric’s Change. Parlor Press.

- Audring, J. (2009). Reinventing pronoun gender.

- De Vos, L., De Sutter, G., & De Vogelaer, G. (2021). Weighing psycholinguistic and social factors for semantic agreement in Dutch pronouns. Journal of Germanic Linguistics, 33(1), 30-66.

- Gustafsson Sendén, M., Bäck, E. A., & Lindqvist, A. (2015). Introducing a gender-neutral pronoun in a natural gender language: the influence of time on attitudes and behavior. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 893.

- Gustafsson Sendén, M., Renström, E., & Lindqvist, A. (2021). Pronouns beyond the binary: The change of attitudes and use over time. Gender & Society, 35(4), 588-615.

- Milles, K. (2011). Feminist language planning in Sweden. Current issues in language planning, 12(1), 21-33.

- Tavits, M., & Pérez, E. O. (2019). Language influences mass opinion toward gender and LGBT equality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(34), 16781-16786.

- Vergoossen, H. (2015). Cognitive demands of gender-neutral language: the new genderless pronoun in the Swedish language and its effect on reading speed and memory.

- Vergoossen, H. P. (2021). Breaking the Binary: Attitudes towards and cognitive effects of gender-neutral pronouns (Doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Stockholm University).