If you speak more than one language, you might be familiar with this situation: you can’t find a word in one language, but you know it in another. You might find this experience quite frustrating, but what if the person you are talking to speaks the same languages as you? In that case, if you can’t find the word in English, you could say it in Spanish instead. An example of this could be “Give me a hamburger without lechuga please”: in this case the sentence starts in English and the word ‘lettuce’ is substituted with its Spanish counterpart ‘lechuga’. When this language-mixing goes beyond occasionally borrowing a word or phrase, scientists call it ‘code-switching’ and this can be a daily experience for many bilinguals.

Several studies report that switching between languages requires more cognitive effort compared to communicating in one language. This can be seen for example in increased reading times and speech rate. If this is true and code-switching represents more of a burden than an advantage, why do bilinguals code-switch?

Why do bilinguals code-switch?

One theory is that bilinguals code-switch to communicate more efficiently. In daily language use, disfluencies, hesitations and errors are common. You’ve probably never noticed this, but it’s a complicated process to plan out what you’re going to say, and then say it exactly as planned. For bilinguals the situation is even more complicated: when they plan a message, they have to select the right words in the right language, put them in the order that language requires and pronounce the result using the language-appropriate pronunciation. To make this process easier, bilinguals can use several strategies. For example, they can suppress one language entirely to make it easier to speak the other fluently. But, as new research shows, they can also profit from the fact that languages differ in their structure to make planning a sentence easier. How exactly?

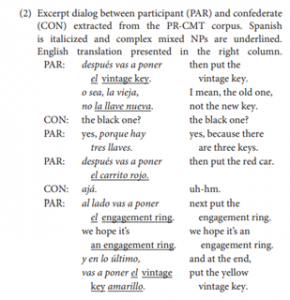

The advantages of code-switching were studied in Spanish-English bilinguals from Puerto Rico, a context in which Spanish is the dominant language for interacting with family, but English exposure comes from media and education. During the experiment, each participant was shown a picture with several objects, like in the image below. They had to describe the objects that they saw and their position to one of the researchers (who the participant thought was another participant). Some objects were very similar to each other; for example, there were three types of keys and two types of gloves. On the right side you can see an example of the conversation that participants had with the researcher, and its translation in English on the right. (Note that “PAR” denotes the parts of the conversation said by the participant and “CON” the parts that were said by the researcher pretending to be another participant.)

What’s really important to know is that English and Spanish have different syntactic rules when it comes to the order of words in a sentence: in English the adjective (underlined) precedes its noun (in bold), while in Spanish the adjective follows its noun:

EN: I eat a green apple.

ESP: Como una manzana verde.

This difference in the word order of English and Spanish makes planning a message more complicated for bilinguals. Because it’s important to select the right word order for the desired language, we wouldn’t expect to see bilinguals code-switch in an adjective + noun phrase. However, the authors found the opposite effect: participants produced simple sentences more frequently in Spanish only (that is, without code-switching), while code-switching occurred more often in complex sentences, including in adjective + noun phrases, like you can see in the example conversation above. How can we explain this?

Code-switching can be strategic

Bilinguals can choose, in situations when it benefits them, to take advantage of the fact that languages differ in their structure. In this task, participants sometimes had to describe similar objects (such as the three different keys). In such a situation, referring to its (unique) characteristics first may help the listener to figure out more quickly which object the speaker is referring to:

Después vas a poner el vintage key.

Then put the vintage key

Al lado vas a poner el engagement ring.

Next put the engagement ring

So, in this specific task, bilinguals preferred to switch to another language for complex noun + adjective structures. In other words, they chose to use the word order of English if they thought this would make it easier for the listener to understand which object they were describing.

Another thing this study shows is that code-switching doesn’t only occur when the speaker is speaking in their second language. Some bilinguals like to code-switch in their mother tongue. The same has been confirmed in a study with Spanish-English bilinguals living in Texas: they code-switch more when they are communicating in Spanish (their mother tongue) than in English. This interesting finding shows that the language you acquired first does not necessarily have a special status: you don’t necessarily know more words in that language and it is not always the one that is accessed most quickly. How often and when you use that language are other important variables that can play a role in determining which language is accessed first and which is more likely to be used when code-switching.

To sum up, code-switching refers to the mixing of words from two languages in the same sentence; this can occur quite frequently in bilinguals both when speaking their mother tongue and their second language. We learned that code-switching can require more cognitive effort for the speaker compared to communicating in one language only, but it can also be used in some situations as a helpful strategy to communicate more efficiently.

Read further:

- Beatty-Martínez AL, Navarro-Torres CA and Dussias PE (2020) Codeswitching: A Bilingual Toolkit for Opportunistic Speech Planning. Front. Psychol. 11:1699. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01699. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01699/full

- Heredia RR & Altarriba J. (2001) Bilingual Language Mixing: Why Do Bilinguals Code-Switch? Current directions in Psychological Science 10(3), 164-168. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/1467-8721.00140

- Özşen, A., Çalışkan, T., Önal, A., Baykal, N., & Tunaboylu, O. (2020). An Overview of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education. Journal of Language Research (JLR) 4(1), 41-57. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jlr/issue/54148/795090

Writer: Sara Mazzini

Editors: John Huisman

Dutch translation: Inge Pasman

German translation: Barbara Molz

Final editing: Eva Poort