1. What was the main question in your dissertation?

The main question of my dissertation was how well we remember things we say compared to things we hear, especially in a conversation.

Language and memory are both very important aspects of our ability to perceive and interact with the world around us. But even though we know they interact, we don’t know how. Decades of research on memory have shown that we remember words we come up with ourselves better than words that we read. Similarly, we remember words we say aloud better than words we say silently in our heads. Clearly, then, it must be the case that our memory is influenced by speaking in some way or another. In my PhD, I studied why and how our memory benefits from speaking.

3. Why is it important to answer this question?

Getting a better idea of how language and memory interconnect is crucial for our understanding of human cognition. Another element to my work is that I studied the relationship between memory and language in the context of a conversation. This is pretty unusual, because it is very difficult to study conversations. However, I think it is really important to research language in a communicative context – communication is, after all, one of the basic purposes of language.

4. Can you tell us about one particular project?

The project I was most excited about is the one in which I actually got two participants in the lab talking to each other. The challenge here was to design an experiment during which participants could interact, but interact in a way that allowed me to investigate the things I wanted to investigate. That is, at any given time I wanted them to be saying certain words, that I had controlled to be equally memorable, rather than talking about what they ate last night or what their favourite sports team was. In the end, we settled on a design in which participants sat in front of a screen and could not see the other participant’s screen.

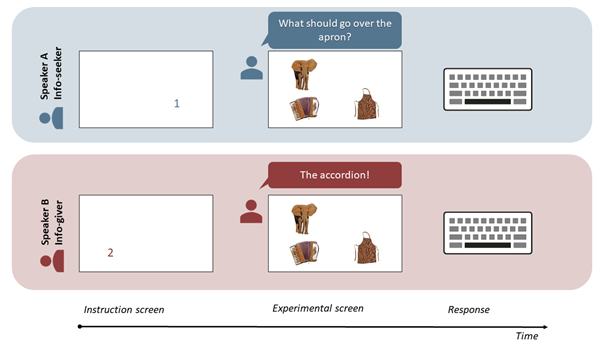

On the screen, different pictures of objects appeared. One of the participants was the “information-seeker” who would ask something about the objects on the screen, and the other participant was the “information-giver” who would give the answer. Before the pictures appeared, the information-seeker saw a “1” in one of the places a picture could occur. This signaled that, when the pictures appeared, they should ask something about the picture that appeared where the “1” was. The information-giver saw a “2” on one of the places where a picture could occur, which indicated that in their answer they should say something about the picture that would occur where the “2” was (see figure 1). When the pictures appeared, the information-seeker asked: “what goes next to the…” and then named the object that had appeared in the place of the “1”. The information-giver then answered by naming the picture that had appeared in the place of the “2”. This went on for a while: the information-seeker asked something about one of the pictures, and the information-giver answered by naming one of the other pictures. A day later, each participant completed a memory test where they saw the names of the pictures they previously talked about, as well as some new object names. For each object name, they had to indicate whether they had “talked” about it the day before.

5. What was your most interesting/ important finding?

I was really excited about the finding from the project I just described. I found that information-seekers had good memory for the objects they asked a question about, and -more interestingly- also had pretty good memory for the object their partner mentioned in their answer. Information-givers on the other hand didn’t have as good a memory for the object their partner asked about, but did remember the objects of their own answer. I’m excited by this finding because it shows that the reason someone is having a conversation can affect what they remember from it. If someone starts a conversation with the intention to get new information, they really do remember this new information. However, the one in the conversation that only provides the answer and does not really have any intention to gain new information, does not remember as much from the conversation, as they mostly remember what they had said themselves.

Sadly, I wasn’t able to finish data collection because of the outbreak of COVID-19, so as excited as I am by these results, they remain preliminary.

6. What are the consequences/ implications of this finding? How does this push science or society forward?

I believe that this finding underlines the importance of conducting psycholinguistic research in ways that better resemble everyday communication. Dynamics such as someone’s role and interest in a conversation can have a real impact on the effects we’re interested in as psycholinguists. However, we often miss those dynamics by testing people one-by-one and stripping language of its communicative function in our labs.

7. What do you want to do next?

During my PhD I became quite convinced that scientists have a lot to gain by working openly, transparently, and reproducibly. In the last few years, I taught myself and others how to make research more open and reproducible. I’m happy to say that this is now my full-time job, working as a trainer on research data management and open science at the Delft University of Technology.

Read further

– Link to dissertation

Pictures

– Figure 1: own production

Interviewer: Merel Wolf

Editing: Julia Egger

Dutch translation: Inge Pasman

German translation: Fenja Schlag

Final editing: Merel Wolf