Meaning is a fundamental aspect of language, which captures the way we categorise and organise our experiences of the world around us. The great diversity in human cultures has created as many languages, all expressing the experience of its speakers. Differences in word meaning can therefore pop up in unexpected places. For example, when I started learning Japanese, I learned that the word for ‘blue’ is ao (Figure 1). However, later I found out that a ‘green’ traffic light is also called ao. The meaning of ao is therefore sometimes described as ‘grue’ (= green + blue), as it covers both what English would call green and blue shades–another example is aomono for ‘vegetables’; eat your ‘greens’!

It might make sense that different languages carve up the colour spectrum differently, because individual speakers can differ in their colour vision -remember the dress?- but what about something like body parts? Our world starts with our body. We use our hands as tools, our legs to get us places, and our sensory organs to perceive. It is therefore no surprise that all languages have terms for parts of the body. Surely this central role of the human body means that everyone thinks about its parts the same way? As I found out while doing linguistic fieldwork in Japan, this is not necessarily the case.

Okinawan is a language spoken in the south of Japan. It is related to Japanese much like English is related to German or Dutch. Sometimes words differ only in their pronunciation: Okinawan uses tii for ‘hand’, which is te in Japanese. Other times, different terms are used altogether: ‘arm’ is ude in Japanese, but Okinawa uses keena instead. I just had to remember the new label. Or so I thought. During one of my interview sessions, someone said “My tii really hurts!” while grabbing the muscly bit of their forearm. But wait, keena is arm, so what was going on here? It turns out that tii means more than just ‘hand’.

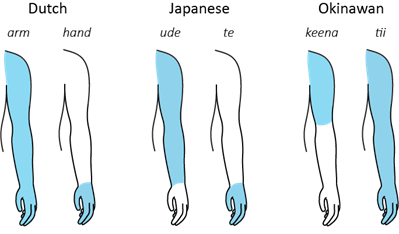

In order to find out what people actually refer to when using terms like hand or arm, we can ask them to colour in those body parts in a drawing of the human body. This method reveals how languages can differ in body parts categories. As a previous study already looked at differences between Dutch arm and hand versus Japanese ude and te, it was only a small step for me to ask Okinawan speakers to colour in keena and tii. As it turns out, the three languages all slightly differ in how they think of the different body parts (Figure 2). What is interesting here is that Okinawa does not have a word that refers to the hand, and only the hand, which is a body part that has been previously thought to be expressed in every language.

Investigating diversity like this helps uncover systematicity in the variation between languages. Also, it increases our understanding of the nature and limits of language itself. It helps us answer questions like ‘are some categories more commonly distinguished than others’? This is especially important for body-part terms, as many languages use these to talk about other things as well: a head of state, speaking in tongues, or the foot of a hill. Interestingly, Japanese has no specific word to refer to the ‘foot’—i.e. the part from the ankle to the toes—and the translation equivalent of ‘the foot of a hill’ does not refer to any body parts. Studying how different languages divide the body into parts can therefore help us understand how people think and talk about the world. So, when learning a new language, you also learn to look at the world differently–is the traffic light ‘blue’ or ‘grue’? Or, next time you need assistance, make sure you know whether to ask someone to lend you a hand or an arm.

Read more

– Kraska-Szlenk, I. (2014). Semantic extensions of body part terms: Common patterns and their interpretation. Language Sciences, 44, 15–39.

– Majid, A., & van Staden, M. (2015). Can Nomenclature for the Body be Explained by Embodiment Theories? Topics in Cognitive Science, 7(4), 570–594.

Pictures

– Figure 1 and 2: own production

Writer: John Huisman

Editor: Alessio Quaresima

Dutch translation: Caitlin Decuyper

German translation: Bianca Thomsen

Final editing: Merel Wolf